For the last five years, the recipe for AI progress has been remarkably simple: take a neural network, add more data, add more compute, and watch the intelligence line go up. This was the Age of Scaling. It was an era of industrial certainty, where companies could pour billions into hardware with the confidence of a guaranteed return.

But according to Ilya Sutskever, that era is drawing to a close.

In a recent interview with Dwarkesh Patel, Sutskever argued that we are leaving the Age of Scaling (roughly 2020–2025) and entering the Age of Discovery (or Research). Here is why the rules of the game are changing, and what that means for the future of AI.

The Age of Scaling: When “More” Was Enough

Sutskever characterizes the period between 2020 and 2025 as a time when a single insight—pre-training—sucked the air out of the room.

The “scaling hypothesis” wasn’t just a theory; it was a business plan. It told executives exactly what to do: “If you mix some compute with some data into a neural net of a certain size, you will get results.” It was low-risk and high-reward. Because everyone knew the recipe worked, execution became more important than ideation.

“Scaling sucked out all the air in the room,” Sutskever noted. “We got to the point where there are more companies than ideas.”

But this strategy relied on a resource that is now dwindling: pre-training data. The internet is finite. We have scraped the text of humanity, and while synthetic data and “souped-up” pre-training offer some runway, the era of simply 100x-ing the dataset to get a 100x smarter model is effectively over.

The Competitive Programmer vs. The Natural Talent

To explain why current models fall short despite their massive scale, Sutskever offered a striking analogy involving two students:

-

Student A (The Model): Wants to be the best competitive programmer. They practice for 10,000 hours, memorize every proof technique, and solve every problem ever written. They become a machine at coding competitions.

-

Student B (The Human): Practices for 100 hours. They have the “it” factor—a deep, intuitive understanding of the underlying logic.

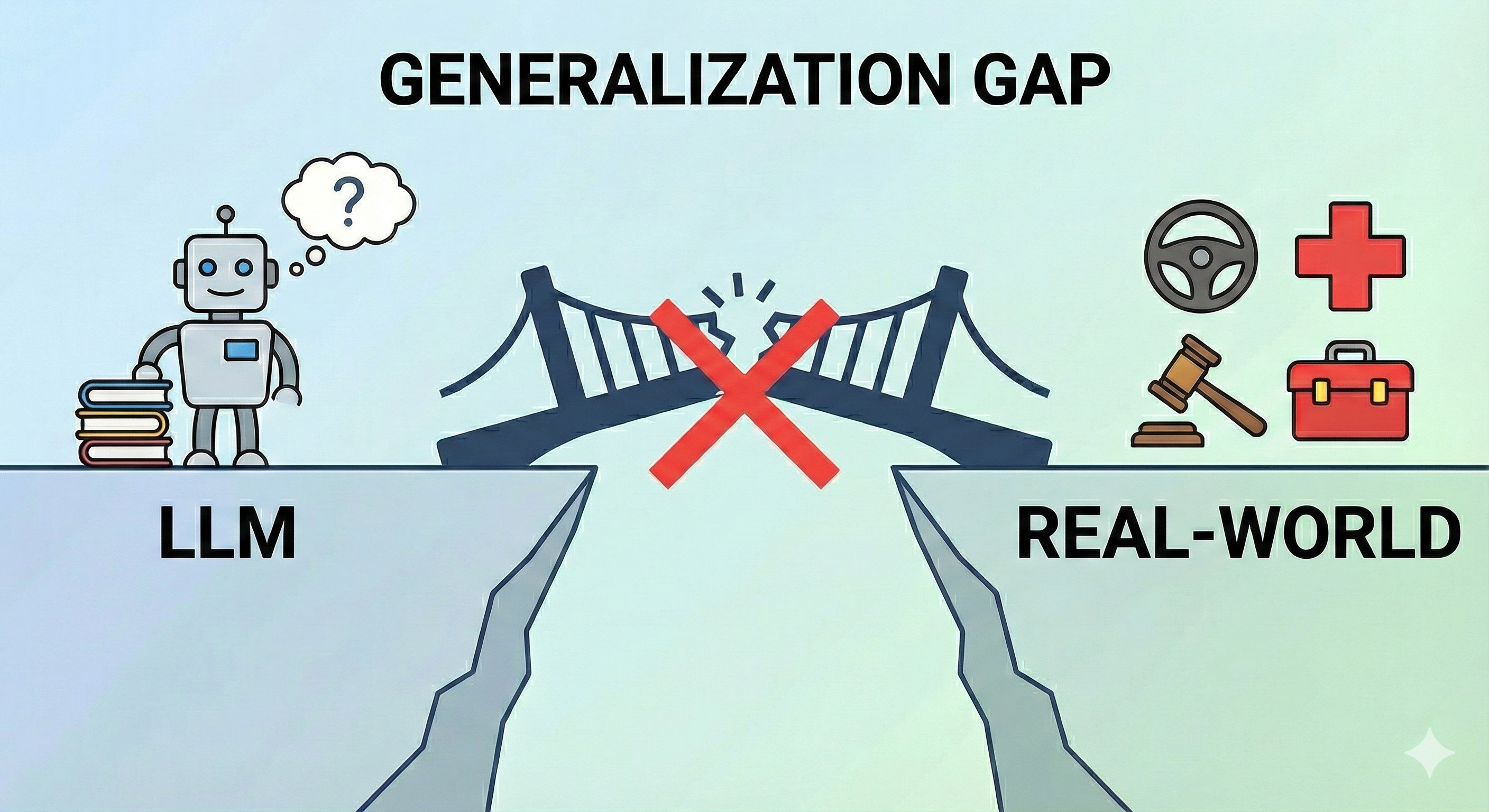

Currently, LLMs are Student A. They have “memorized” the internet’s worth of patterns (the 10,000 hours), but they lack the fundamental “it” factor that allows Student B to generalize to entirely new domains with minimal effort.

This is the Generalization Gap. Humans are shockingly sample-efficient. A teenager learns to drive not by crashing a million cars in a simulation, but by understanding the physics of the world and applying it. Models, by contrast, require oceans of data to learn what humans grasp intuitively.

Emotions as “Value Functions”

To bridge this gap, Sutskever offered a fascinating technical analogy for human emotion. He suggested that emotions act as a “value function”—a pre-programmed evolutionary guide that helps humans navigate decisions without needing immediate external rewards.

Current RL (Reinforcement Learning) models often need massive amounts of trial-and-error data to learn a task because they lack this internal compass. They essentially have to “crash the car” thousands of times to learn that crashing is bad.

If we can discover how to build the equivalent of these “internal value functions” into AI, models could learn much faster and behave more robustly. They would effectively “feel” when an action is wrong or dangerous without needing to be explicitly told, moving us closer to the sample efficiency of biological intelligence.

Entering the Age of Discovery

If the Age of Scaling was about engineering (building bigger pipes for data), the Age of Discovery is about research (figuring out what to put in the pipes).

Sutskever argues we are returning to a dynamic similar to 2012–2020, where progress wasn’t guaranteed by a formula but won through tinkering, insight, and failure.

Key Characteristics of this New Era:

-

Ideas > Compute: While you still need massive compute to train the final system, you don’t need the world’s largest supercomputer to discover the next breakthrough. The Transformer architecture (which powers ChatGPT) was discovered on just 8 to 64 GPUs.

-

Risk Returns: Companies can no longer treat AI investment like a treasury bond with fixed yields. Research is inherently uncertain. You have to say, “Go forth, researchers, and find something,” knowing they might come back with nothing.

-

Beyond Pre-training: The next leap won’t come from reading more text. It will come from new paradigms—perhaps breakthroughs in how models “reason” during inference (like OpenAI’s o1), or new ways to instill the “values” and robust generalization that humans possess.

The Economic Lag

Sutskever also touched on a paradox: Why do models crush benchmarks (evals) but struggle to transform the economy instantly?

His theory is that we have “over-fit” to benchmarks. By feeding models massive amounts of data related to coding competitions and exams, we’ve created “Student A”—savants who can ace a test but stumble when asked to fix a messy, real-world software bug without introducing two new ones. The economic impact will only catch up when we solve the reliability and generalization problem, not just the test-taking problem.

Conclusion

The “Age of Discovery” is exciting, but it is also more dangerous for incumbents. In the Age of Scaling, the winner was whoever had the biggest checkbook. In the Age of Discovery, the winner is whoever has the best ideas.

As Sutskever puts it, “Scaling is just one word… but now that compute is big… we are back to the age of research.”

The easy growth is over. Now the real science begins.